1029301

Franklin D. Roosevelt

In apparently his first letter after Japan attacked Pearl Harbor,

FDR writes of his son amid hysteria that Japan might attack California:

“My boy Elliott has just been ordered to a bombing squadron on the West Coast.”

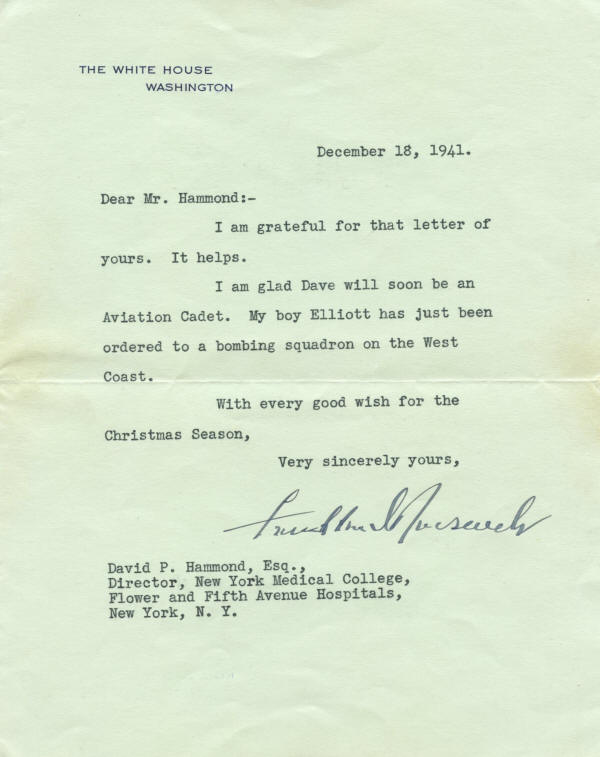

Franklin Delano Roosevelt, 1882–1945. 32nd President of the United States, 1933–1945. Rare and excellent World War II content Typed Letter Signed, Franklin D. Roosevelt, one page, with integral leaf attached, 7” x 9”, on stationery of The White House, Washington, [D.C.], December 18, 1941.

This beautiful and poignant letter, which appears never to have been on the autograph market before, is the earliest of only four Roosevelt letters dated in December 1941 that we have found. Writing a mere 11 days after Japan's December 7 attack on Pearl Harbor, and amid widespread fear of a Japanese attack on the American mainland, Roosevelt has his mind on his son, Elliott, who has been ordered to a West Coast bomber squadron.

Roosevelt replies to an encouraging letter from David P. Hammond, the director of the New York Medical College. Hammond had written in response to Roosevelt’s December 9 radio fireside chat. He called Roosevelt a “man of vision and great courage,” said that his son, Dave, expected to become an aviation cadet, and offered his own service to the Army medical corps. In reply, the President writes: “I am grateful for that letter of yours. It helps. / I am glad that Dave will soon be an Aviation Cadet. My boy Elliott has just been ordered to a bombing squadron on the West Coast.” He concludes by sending “every good wish for the Christmas Season. ”

In As He Saw It, Elliott Roosevelt recounted his father’s reaction when he learned that Elliott had enlisted in the Army Air Force in 1940. “He glanced at the piece of paper with my orders on it and looked up with tears in his eyes,” Elliott wrote. “I was the first of his sons to volunteer. He couldn’t speak for a moment. Then, ‘I’m very proud of you.’ His emotion made me pretty proud, myself. That weekend the whole family was at Hyde Park . . . and that evening, at dinner, Father lifted his glass and proposed a toast: ‘To Elliott. He’s the first of the family to think seriously enough, and soberly enough, about the threat to America to join his country’s armed forces. We’re all very proud of him. I’m the proudest.’”

President Roosevelt was, quite naturally, extremely busy in the days following Pearl Harbor. Yet his mind was quite obviously on his son Elliott—and the danger that he faced from a potential Japanese West Coast invasion. He said nothing in this letter about his youngest son, John, who enlisted in the Navy after Pearl Harbor, although Hammond had mentioned having a photo of John together with Dave and had said nothing about Elliott. Hence the rarity and importance of this letter.

This timeline shows just how busy FDR was:

● On December 7, following notification of the attack, he received damage reports from the Navy Department; spoke by telephone with Secretary of the Treasury Henry Morgenthau, Jr., about freezing Japanese assets, securing the borders, and posting additional security around the White House; met with Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson, Jr., Secretary of the Navy William F. Knox, and others at 3:05 p.m.; met with Secretary of State Cordell Hull and General George C. Marshall at 3:20 p.m.; worked on a proposed message asking Congress to declare war on Japan; met with Solicitor General Charles H. Fahy at 7:00 p.m.; held a special cabinet meeting at 8:30 p.m. to discuss the proposed message; met with Vice President Henry A. Wallace and congressional leaders at 9:45 p.m., following the cabinet meeting; met with Under Secretary of State Sumner Welles at 10:45 p.m.; and finally, at 12:00 midnight, met with journalist Edward R. Murrow and Coordinator of Information Col. William J. Donovan.

● On December 8, he addressed a joint session of Congress at 12:30 p.m., requesting and receiving a congressional declaration of war against Japan, officially bringing the United States into World War II.

● On December 9, he communicated with British Prime Minister Winston S. Churchill about a meeting later that month, held his usual Tuesday press conference, and then worked on and later delivered his radio fireside chat that night in which he tied the Japanese attack to Germany and Italy. He argued that Japan’s course “for the past ten years in Asia has paralleled the course of Hitler and Mussolini in Europe and in Africa. Today, it has become far more than a parallel. It is actual collaboration so well calculated that all the continents of the world, and all the oceans, are now considered by the Axis strategists as one gigantic battlefield.”

● On December 10, he received news that the Japanese had attacked and sunk the British battleship Prince of Wales and its accompanying cruiser, Repulse, in a two-hour battle off Malaya.

● On December 11, Adolf Hitler derided Roosevelt before the German Reichstag as “the man who is the main culprit in this war,” one who, “while our soldiers are fighting in snow and ice, . . . likes to make his chats from the fire-side.” Germany thereupon declared war on the United States, and Benito Mussolini”s Italy followed suit immediately. Roosevelt then sent Congress a written message asking it to declare war on Germany and Italy, which it did at 3:05 p.m. In addition, acting on the suggestion of CIO Vice President Sidney Hillman, Roosevelt called a conference of labor and industrial leaders to begin in Washington on December 17 “to consider the problem of labor disputes during the war.”

● On December 14, as Roosevelt continued to communicate with him, Churchill set sail for the United States aboard the new battleship Duke of York.

● On December 18, the day he wrote this letter, Roosevelt appointed a commission under the chairmanship of Supreme Court Justice Owen J. Roberts to investigate the Pearl Harbor attack.

● On December 22, Churchill arrived at the White House for more than a three-week stay, the historic “Arcadia Conference,” which ended January 14, 1942.

During this time, Roosevelt wrote several memoranda to cabinet officers and others, but we have found only three other letters from December 1941. Those were to Massachusetts Senator Henry Cabot Lodge, Lady Clementine Churchill, and Morgenthau. On December 23, Roosevelt wrote Lodge declining to authorize funds to dredge a seaplane channel in Boston Harbor because it was not “definitely important to the national defense program.” On December 25, he sent Christmas greetings to Lady Churchill, writing—actually by cablegram—that it “is a joy to have Winston with us” and expressing “how grateful I am to you for letting him come.” On December 28, Roosevelt wrote Morgenthau about the need to help the Soviet Union because the “whole Russian program is so vital to our interests.” Those letters lack the personal poignancy of this one—and thus give context to Roosevelt’s thoughts here.

This letter does not appear in F.D.R. His Personal Letters 1928-1945, part of the four-volume set of Roosevelt’s personal correspondence that Elliott Roosevelt edited and published following FDR’s death.

Roosevelt has signed this letter with a bold, 3¾” fountain pen signature. The letter shows a bit of handling and has minor soiling along the ends of the horizontal fold, but it is not as pronounced as the scan suggests. Overall the letter is in fine to very fine condition. It comes with a copy of Hammond’s letter to FDR from the archives of the Franklin D. Roosevelt Library.

Unframed.

_____________

This item has been sold, but

click here to see other

Presidents and First Ladies items

that we are offering.