1105701

Emperor Napoleon III

”On the same spot where, like cowards, they wanted to shoot us, the government is ordering us to raise the same flag, to shout the same words that unleashed their rage a year ago. What wretched comedy. . . . Today ‘long live the Emperor’ means: long live the imaginary memory of a man that we have feared and hated all our lives, long live the memory of the man, but death to his national system, his family, his high thoughts, his immortal precepts!”

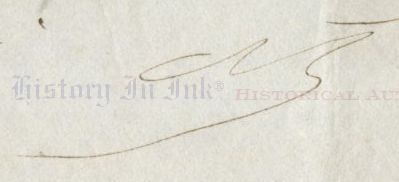

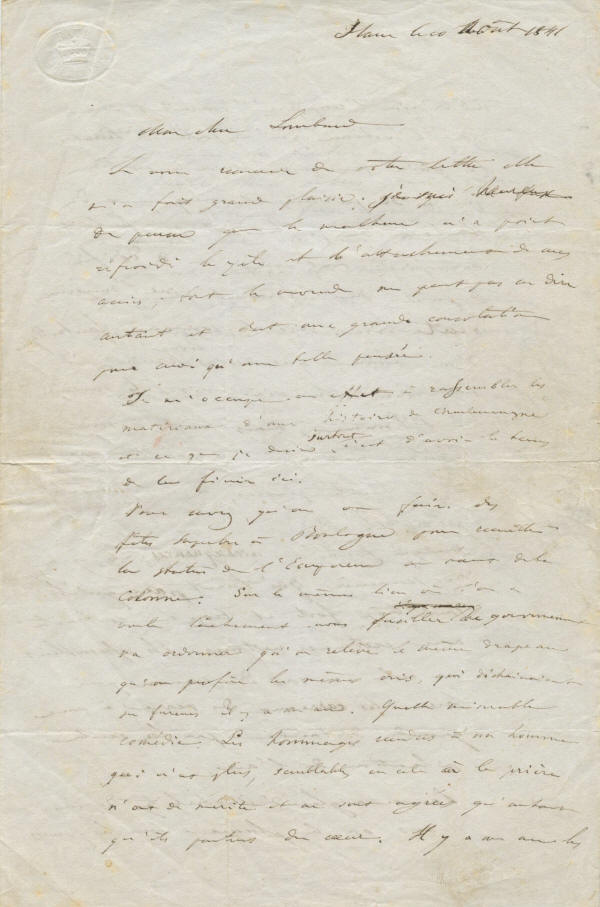

Charles Louis Napoleón Bonaparte, 1808-1873. President of the Second French Republic, 1848-1851; Emperor of the Second French Empire, 1851-1870. Superb Autograph Letter Signed, NB, three pages, octavo, with integral leaf attached, on blind-embossed stationery, Ham, Somme, France, August 10, 1841. In French, with translation.

This is a superb piece—it is the finest letter of Napoleon III that we have seen, and our search of auction records has found no better one. Here the future emperor, imprisoned for staging an attempted coup d'état against the French government at Boulogne-sur-Mer, angrily vents to one of his conspirators, "friend Lombard." He rails against the government's hypocrisy and condemns its faint praise for his uncle, Emperor Napoleon I, whose legacy he says the government has destroyed. In the end, he confidently, although obliquely, predicts his own future rule.

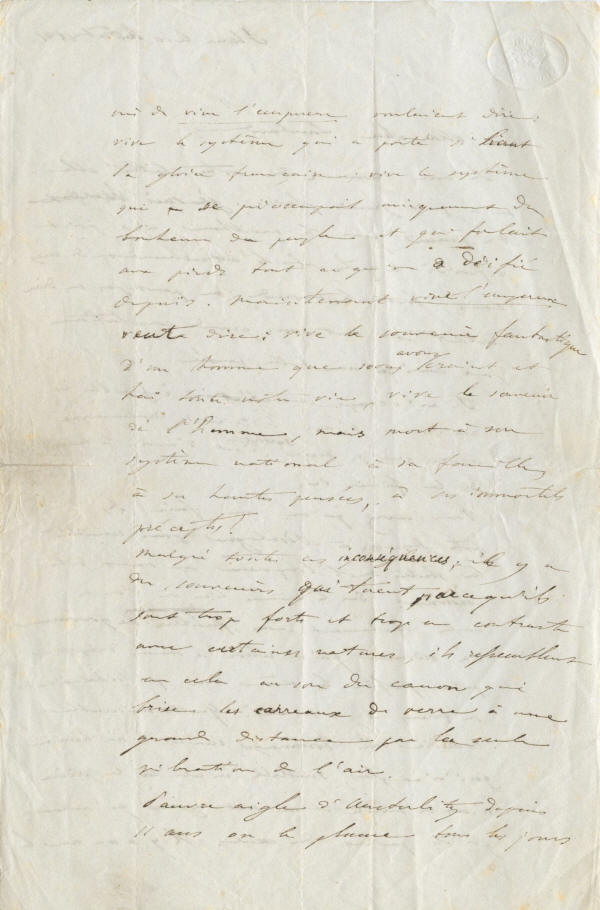

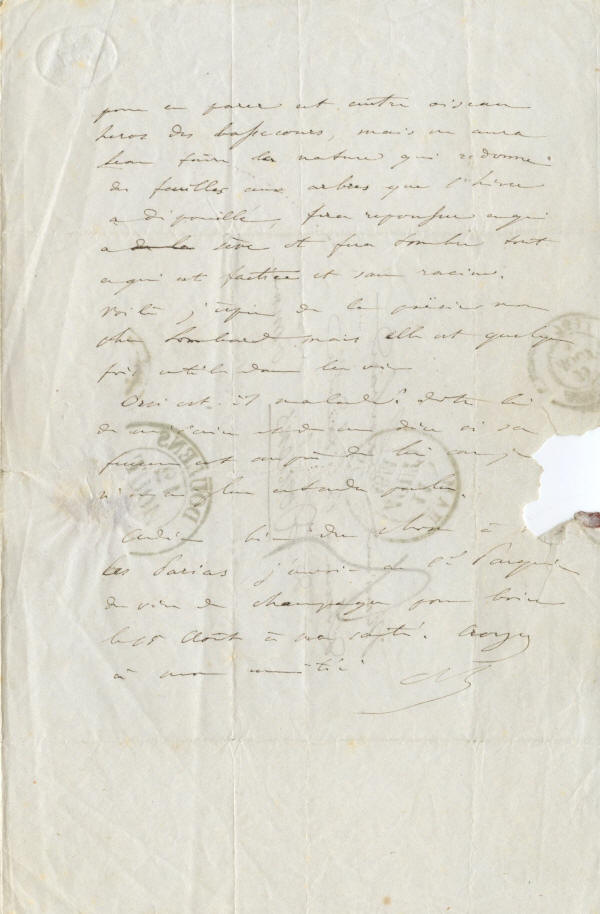

The letter reads, in full: “Dear friend Lombard / I thank you for your letter that has given me great pleasure. I am happy to think that unhappiness has not dampened the zeal and attachment of my friends; not everyone can say the same and such a thought gives me great consolation. / In fact, I am busy collecting materials for a history of Charlemagne and what I desire above all is to have the time to finish it here. / You know that Boulogne will have superb parties on the occasion of erecting the Emperor’s statue on top of the column. On the same spot where, like cowards, they wanted to shoot us, the government is ordering us to raise the same flag, to shout the same words that unleashed their rage a year ago. What wretched comedy. The homage paid to a man that is no more, like an undeserved prayer, is not as true as that which comes from the heart. A year ago the shouts ‘long live the Emperor’ meant ‘long live the system’ that has carried French glory so high, long live the system that has concerned itself only with the happiness of the people and that wants at its feet all that we have defied since. Today ‘long live the Emperor’ means: long live the imaginary memory of a man that we have feared and hated all our lives, long live the memory of the man, but death to his national system, his family, his high thoughts, his immortal precepts! / In spite of all those inconsequentials, there are memories that kill because they are too strong and too much in contrast with certain natures, they resemble the sounds of the cannon that break windows at a great distance through only the vibration of the air. / Poor eagle of Austerlitz, for 11 years one plucks its feathers every day to cut it down to the lesser size of another heroic bird, but nature has done well to give back the leaves of trees that winter has defoliated; all that rises will submerge and will make fall all that is artificial and without roots. / So I hope for poetry my dear Lombard, but it is sometimes useful in life. / Is Orsi sick ? Tell him to write me and tell me about his wife and about him because I haven't heard any more from him. Good riddance to things of pariahs. I have sent C Parquin a bottle of Champagne to drink on the 18th of August to my health! Believe in my friendship . . . ”

The letter stems from Louis Napoleon's desire to rule France. From childhood, he saw himself as an emperor. He was forced to live outside of France, however, after the French banished the Bonapartes and confiscated their property in 1816 following the exile of Napoleon I to the island of St. Helena. Louis Napoleon failed in an attempted coup d'état at Strasbourg on October 30, 1836, and was himself exiled by King Louis Philippe, who treated him mercifully at the time.

The first failed coup did not deter him. Less than four years later, on August 6, 1840, Louis Napoleon failed in a second attempted coup. Leading a small band of 56 loyal supporters, including Lombard, Orsi, and Parquin, he sought to provoke an uprising at Boulogne-sur-Mer, which he hoped would draw General Bernard Pierre Magnan to Lille and allow Louis Napoleon, in turn, to march upon Paris. He was defeated at Boulogne, however, and was captured and tried, along with his conspirators, by the Chamber of Peers.

At his trial, he urged the Peers not to "believe that, yielding to a personal ambition, I wished to attempt in France, and against the nation's will, to restore the Empire." Instead, he explained, “the vote of four millions of citizens which elevated my family imposed upon us the duty of making an appeal to the nation, and of consulting the popular will." Thus, he suggested, he sought only to let the French people make a “free decision" between “[r]epublic or monarchy, empire or royalty." He did not persuade the Peers, and he was convicted and sentenced to perpetual imprisonment. This time, King Louis Philippe was more severe. On December 15, 1840—the day that the repatriated body of Napoleon I was interred at Les Invalides in Paris—Louis Napoleon was imprisoned in the fortress at Ham.

In this letter, written from Ham, Louis Napoleon notes ironically to his friend that the French government intended to place a statue of Napoleon I at Boulogne on the spot of their capture. The statue, erected in a renewal of French national pride, tops a 175-foot column marking the camp at which Napoleon I amassed France's largest-ever army, 80,000 men, ready to invade England. ”Boulogne will have superb parties on the occasion of erecting the Emperor’s statue on top of the column," Louis Napoleon writes. ”On the same spot where, like cowards, they wanted to shoot us, the government is ordering us to raise the same flag, to shout the same words that unleashed their rage a year ago. What wretched comedy.”

He then assails the French government's hypocrisy, taking aim at its rejection of Bonapartism—and, inferentially if not expressly, of Louis Napoleon himself. ”The homage paid to a man that is no more, like an undeserved prayer, is not as true as that which comes from the heart,” he says. ”A year ago the shouts ‘long live the Emperor’ meant ‘long live the system’ that has carried French glory so high, long live the system that has concerned itself only with the happiness of the people and that wants at its feet all that we have defied since. Today ‘long live the Emperor’ means: long live the imaginary memory of a man that we have feared and hated all our lives, long live the memory of the man, but death to his national system, his family, his high thoughts, his immortal precepts! ”

While he dismisses these things as "inconsequentials,” he acknowledges, with a degree of melancholy, that still "there are memories that kill because they are too strong and too much in contrast with certain natures." He complains that 11 years of rule under King Louis Philippe, who obtained the throne following the July Revolution in 1830, had systematically destroyed the glory that France had under Napoleon I. ”Poor eagle of Austerlitz,” he says, referring to Napoleon's greatest military victory, ”for 11 years one plucks its feathers every day to cut it down to the lesser size of another heroic bird . . . ." He had made a similar declaration at his trial the year before: Referring to the July Revolution, he had said, “When, in 1830, the nation reconquered her sovereignty, I thought that the morrow of victory would be as honest as the conquest itself, and that the destinies of France were settled forever. But the country has undergone the sad experience of the last ten years."

Still, with more than a hint of confidence, Louis Napoleon obliquely foretells his own future rule. He writes that ”nature has done well to give back the leaves of trees that winter has defoliated; all that rises will submerge and will make fall all that is artificial and without roots.”

In closing, he writes of two other imprisoned conspirators. He asks about the health of Orsi, who had been sentenced to five years, urging Lombard to tell Orsi ”to write me and tell me about his wife and about him.” He then notes with delight that he had ”sent C Parquin a bottle of Champagne to drink on the 18th of August to my health!” At the trial, Parquin had openly acknowledged his relationship with Louis Napoleon as both his friend and aide-de-camp, although he declared that he was free of all military obligations and denied that he had tried to tamper with French officers, and had said that he shared “the misfortune of this young prince, who has for many long years honored me with his friendship, and to whom I have vowed to give all the devotion of which I am capable." Like Lombard, Parquin had received a 20-year sentence.

Louis Napoleon escaped from the Ham fortress in 1846 and lived in England until the French established a republic with the overthrow of King Louis Philippe in 1848. He returned to France for a short time before returning to England at the request of the provisional government. While in England he was elected to the French Constituent Assembly created to draft a new constitution. On December 10, 1848, the first direct election under the constitution of the Second Republic, Louis Napoleon was overwhelmingly elected President of France. When the National Assembly refused to amend the constitution so that he could serve a second term, Louis Napoleon staged another coup d'état and seized dictatorial powers on December 2, 1851—the 47th anniversary of the crowning of Napoleon I as emperor and the 46th anniversary of Napoleon I's victory at Austerlitz. He reigned as Emperor Napoleon III until 1870, when he was captured during the Franco-Prussian War and was deposed by forces of the Third Republic in Paris two days later.

He has penned this letter in black. The stationery has the blind-embossed crown stamp of a British stationer in Bath at the upper left. A small portion of the red wax seal is intact. There are a seal tear in the margin of the integral leaf, which slightly affects a couple of words of the text, and some bleed through from postal cancellations, which are not particularly obtrusive and do not obscure the text. The signature is unaffected. The letter has normal mailing folds and shows some wrinkling from handling. Overall it is in fine condition.

Letters of Louis Napoleon, Emperor Napoleon III, are rare with outstanding content, and we know of none better than this. This belongs in the finest of French or Napoleonic collections.

Unframed.

_____________

This item has been sold, but

click here to see other

World History items

that we are offering.