1222124

Hugo L. Black

From the personal collection of Supreme Court Justice Tom C. Clark

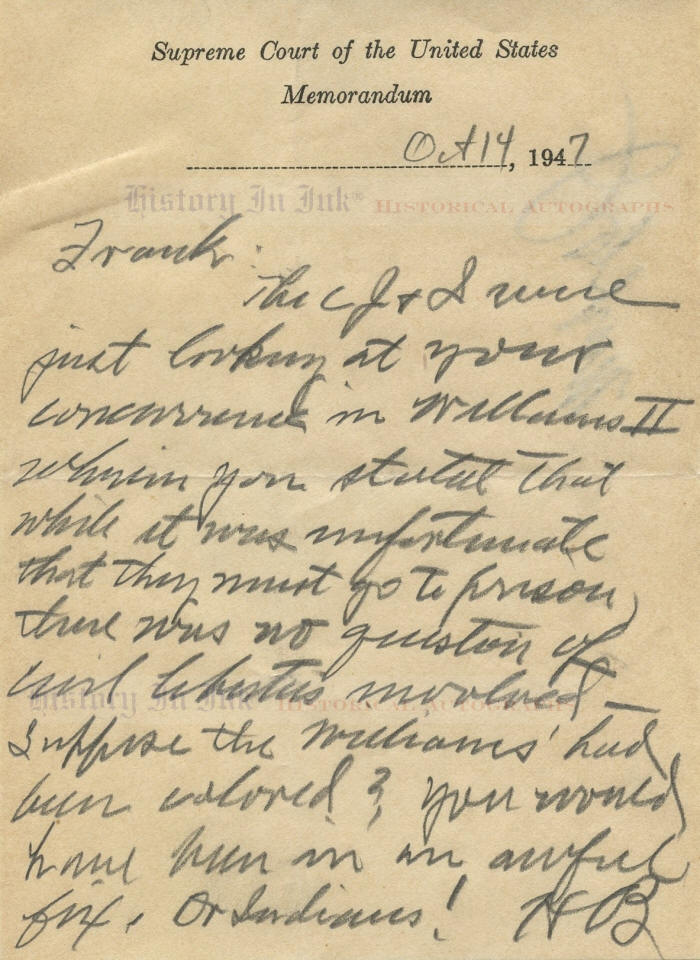

“Suppose the Williams’ had been colored? You would have been in an awful fix. Or Indians!”

Hugo Lafayette Black, 1886–1971. Senator from Alabama, 1927–1937; Associate Justice, United States Supreme Court, 1937–1971. Superb, extraordinarily rare Autograph Note Signed, HB, one page, 4” x 5½”, on stationery of the Supreme Court of the United States, [Washington, D.C.], October 14, 1947.

This is an exceptionally rare internal Supreme Court memorandum from Justice Black to Justice Frank Murphy. Some 2½ years after the case was decided—and almost certainly on the bench during oral argument in two cases that raised similar issues—Black sends a tongue-in-cheek note about Murphy’s concurring opinion in Williams v. North Carolina, 325 U.S. 226 (1945), in which the Supreme Court upheld the bigamous cohabitation convictions of a man and woman in North Carolina on the ground that North Carolina could reexamine the validity of their Nevada divorce judgments. On October 14, 1947, the day Black wrote this note, the Court heard arguments in Scherrer v. Scherrer, 334 U.S. 343 (1948), and Coe v. Coe, 334 U.S. 378 (1948), which challenged Massachusetts’ refusal to give full faith and credit to divorce judgments rendered in Florida and Nevada, as Article IV, § 1 of the United States Constitution requires.

In Williams, the couple was charged under a North Carolina statute providing, in part, that if a person, “being married, shall contract a marriage with any other person outside of this state, which marriage would be punishable as bigamous if contracted within this state, and shall thereafter cohabit with such person in this state, he shall be guilty of a felony and shall be punished as in cases of bigamy.” N.C. Gen. Stat. § 14-183. Justice Felix Frankfurter’s majority opinion said the trial record showed that the couple “left North Carolina for the purpose of getting divorces from their respective spouses in Nevada and as soon as each had done so and married one another they left Nevada and returned to North Carolina to live there together as man and wife.” Neither of the spouses had either been served with process or appeared in the proceedings. When North Carolina charged the couple with bigamous cohabitation, they asserted their Nevada divorces in defense. The Supreme Court majority held that North Carolina had the right to question whether the couple had become domiciled in Nevada, so that Nevada had jurisdiction to enter their divorce decrees. The North Carolina jury found that the couple, “long-time residents of North Carolina, came to Nevada, where they stayed in an auto-court for transients, filed suits for divorce as soon as the Nevada law permitted, married one another as soon as the divorces were obtained, and promptly returned to North Carolina to live.” It was “highly unreasonable,” the Supreme Court said, “to assert that a jury could not reasonably find that the evidence demonstrated” that the couple “went to Nevada solely for the purpose of obtaining a divorce and intended all along to return to North Carolina.” If so, the couple could not have become domiciled in Nevada. The Court thus concluded:

In seeking a decree of divorce outside the State in which he has theretofore maintained his marriage, a person is necessarily involved in the legal situation created by our federal system whereby one State can grant a divorce of validity in other States only if the applicant has a bona fide domicil in the State of the court purporting to dissolve a prior legal marriage. The petitioners therefore assumed the risk that this Court would find that North Carolina justifiably concluded that they had not been domiciled in Nevada. Since the divorces which they sought and received in Nevada had no legal validity in North Carolina and their North Carolina spouses were still alive, they subjected themselves to prosecution for bigamous cohabitation under North Carolina law. The legitimate finding of the North Carolina Supreme Court that the petitioners were not in truth domiciled in Nevada was not a contingency against which the petitioners were protected by anything in the Constitution of the United States. A man’s fate often depends . . . on far greater risks that he will estimate ‘rightly, that is, as the jury subsequently estimates it, some matter of degree. If his judgment is wrong, not only may he incur a fine or a short imprisonment, as here; he may incur the penalty of death.’ . . . The objection that punishment of a person for an act as a crime when ignorant of the facts making it so, involves a denial of due process of law has more than once been overruled. In vindicating its public policy and particularly one so important as that bearing upon the integrity of family life, a State in punishing particular acts may provide that ‘he who shall do them shall do them at his peril and will not be heard to plead in defense good faith or ignorance.’ . . . Mistaken notions about one’s legal rights are not sufficient to bar prosecution for crime.

Black dissented, arguing that the couple was “sentenced to prison because they were unable to prove their innocence to the satisfaction of the State of North Carolina,” “convicted under a statute so uncertain in its application that not even the most learned member of the bar could have advised them in advance as to whether their conduct would violate the law.” Realistically, Black argued, they were “deprived of their freedom because the State of Nevada, through its legislature and courts, follows a liberal policy in granting divorces.”

Justice Murphy, however, agreed to affirm the convictions. He joined the majority opinion but also wrote a separate concurrence. He found that the jury had declared the couple’s actions fraudulent, a fact, he said, that was “supported by overwhelming evidence satisfying whatever standard of proof may be propounded.” He continued:

No justifiable purpose is served by imparting constitutional sanctity to the efforts of petitioners to establish a false and fictitious domicil in Nevada. . . . Nor are any issues of civil liberties at stake here. It is unfortunate that the petitioners must be imprisoned for acts which they probably committed in reliance upon advice of counsel and without intent to violate the North Carolina statute. But there are many instances of punishment for acts whose criminality was unsuspected at the time of their occurrence. Indeed, for nearly three-quarters of a century or more individuals have been punished under bigamy statutes for doing exactly what petitioners have done. . . . Petitioners especially must be deemed to have been aware of the possible criminal consequences of their actions in view of the previously settled North Carolina law on the matter. . . . This case, then, . . . comes as no surprise for those who act fraudulently in establishing a domicil and who disregard the laws of their true domiciliary states.

(Emphasis added.)

It was in light of Murphy’s italicized comments that Justice Black later wrote this note during the oral arguments in Scherrer and Coe. Referring to “Williams II,” since that was the second appeal in that case, he and Chief Justice Fred M. Vinson take a playful poke at Murphy. Black writes, in full: “Frank: The CJ and I were just looking at your concurrence in Williams II wherein you stated that while it was unfortunate that they must go to prison, there was no question of civil liberties involved— Suppose the Williams’ had been colored? You would have been in an awful fix. Or Indians!”

As it turned out, in Scherrer and Coe the majority, including both Black and Vinson, ruled that Massachusetts had to respect the Florida and Nevada decrees. Murphy joined Frankfurter in dissent. Vinson’s majority opinion distinguished Williams on the ground that because the spouses in Scherrer and Coe appeared and participated in the proceedings, the Florida and Nevada courts had found the jurisdictional facts in the context of actual litigation.

Black’s comments in this note, racist by today’s standards, were hardly so when he made them, almost exactly 20 years before Thurgood Marshall become the first African-American to sit on the Supreme Court. Black, an Alabama Democrat who early in his legal career joined but soon resigned from the Ku Klux Klan, staunchly defended the constitutional rights of minorities during the more than 34 years that he served on the Supreme Court. His record as a Justice does not reflect racism. He and Murphy were close friends, however—and indeed Murphy held Black in high esteem—so it seems apparent that this was Black’s good-natured dig at Murphy, perhaps prompted by a question from Murphy or another Justice during the oral argument, and not a racist remark.

Likely Black wrote this note after he and Vinson reviewed Murphy’s Williams concurrence during the oral arguments in Scherrer and Coe. It is not uncommon for Justices to pass notes to each other on the bench during oral argument in cases. Justice John Paul Stevens noted that they have access to “pages sitting behind the bench on seats that are not visible to most people in the courtroom,” have pads “for notes that a page will deliver to a colleague at the other end of the bench,” and sometimes request pages “to obtain a specific court opinion,” often “previous Supreme Court opinions gathered in the volumes shelved in the area immediately behind curtains that are opened when the justices ascend the bench.” John Paul Stevens, Five Chiefs 117 (2011).

Not only is this an absolutely rare piece of internal correspondence between Justices, but it is rare as well because it is written entirely in Black’s hand. Aside from a handwritten note that we also sold, we found only one other handwritten note, and no handwritten letters, signed by Justice Black in auction records over a period of 38 years before we listed this one for sale.

Justice Black has written and signed this note in dark pencil. The paper is toned from age, and there is a paper clip impression in the blank area at the upper left. Black’s notation “Murphy J,” by which he addressed the folded note to Murphy, appears in dark pencil on the back of the note and shows through to the front. The piece is in fine to very fine condition.

Provenance: This note comes from the personal collection of Justice Tom C. Clark, who served on the Supreme Court from 1949 until 1967. Justice Clark collected the autographs of other Supreme Court Justices dating back into the 19th Century. We have been privileged to offer a number of items from the collection. This one comes with the backing page, which bears the federal eagle watermark and Justice Black’s typed name, that Justice Clark inserted behind the item in the page protector used to house this piece his collection. This piece is not laid down to the backing sheet.

Unframed.

_____________

This item has been sold, but

click here to see other

Supreme Court items

that we are offering.