1403331

Dean Rusk

Scroll down to see images of the item below the description

From the Estate of Llewellyn E. Thompson,

United States Ambassador to the Soviet Union

Rusk writes of Ambassador Thompson's "crucial behind the scenes" role during the Cuban Missile Crisis

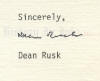

David Dean Rusk, 1909-1994. American Secretary of State, 1961-1969. Typed Letter Signed, Dean Rusk, one page, 8½" x 11", on stationery of The University of Georgia School of Law, Athens, Georgia, November 16, 1987. Accompanied by an Autograph Letter Signed, Steve Rosenfeld, by Washington Post Deputy Editorial Page Editor Stephen S. Rosenfeld, one page, 5" x 7", on stationery of The Washington Post, [Washington, D.C.], November 20, 1987, and a copy of Rosenfeld's column entitled "I Donʼt Agree, Mr. President" from the October 30, 1987, edition of the Post.

Rusk, the Secretary of State during eight tough years of the Cold War under Presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson, underscores Ambassador Llewellyn E. Thompsonʼs vital role during the most dangerous episode of the Cold War—the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis, when the United States demanded that the Soviet Union remove its offensive missiles from Cuba. He writes, in full: “I thank you most warmly for sending me your fine piece about Llewellyn Thompson. I doubt that the full account of Llewellynʼs contribution to the Cuban missile crisis will ever be recorded, but his role proved to be crucial behind the scenes. He was a wise, thoughtful, steady person who was one of the best of our career foreign services officers."

Rusk writes to Rosenfeld, whose article outlined Thompson's insistence that the United States need not trade its missiles in Turkey for the Soviet Union's missiles in Cuba. President Kennedy had virtually resigned himself to the notion that the trade was necessary to end the crisis. Thompson adamantly opposed it, however, and insisted that the United States could draw the Soviets back to their previous, less bellicose position. His advice to Kennedy was largely responsible for avoiding nuclear war with the Soviet Union.

As the United States Ambassador to the Soviet Union under both Kennedy and his predecessor, President Dwight D. Eisenhower, Thompson became well acquainted with the Soviet hierarchy, including Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev, at whose country dacha he stayed as a house guest, an extraordinary honor for a foreign diplomat. He thus was able to provide valuable insight into Soviet thought when Khrushchevʼs blustery inconsistency put Kennedy in a quandary.

In the early evening of Friday, October 26, 1962, as war seemed inevitable, Khrushchev sent Kennedy a conciliatory letter in which he offered to remove Soviet offensive missiles from Cuba if the United States would promise not to invade Cuba. As Kennedy was considering that letter, Khrushchev sent a much more belligerent one early the next morning in which he offered to withdraw missiles from Cuba only if the United States would withdraw similar American missiles from Turkey. The Soviets upped the ante after being misled by columnist Walter Lippmann's October 25 Post column suggesting that the United States would agree to a missile swap—an error that Lippmann, who was close to Kennedy advisor McGeorge Bundy, compounded by telling Soviet Ambassador Anatoly Dobrynin that, although JFK had not authorized the article, Lippmann had talked with officials in the Arms Control and Disarmament Agency.

Thompson argued vociferously against trading away the Turkish missiles because he knew that America's NATO allies would perceive that the United States had abandoned them. He correctly suspected that Lippmann's column caused the change in Soviet thought. Thompson also correctly perceived that Khrushchev did not want war but probably wrote the second letter under scrutiny from Soviet generals and hard-line members of the Politburo. Thompson knew that an American promise not to invade Cuba would let Khrushchev off the hook, since Khrushchev could claim strategic success in avoiding an American invasion. He thus urged Kennedy to respond to Khrushchevʼs conciliatory letter and to ignore the subsequent belligerent one. The ExComm recordings show that Rusk, taking Thompson's position, pushed JFK in that direction. See Sheldon M. Stern, Averting ʻThe Final Failureʼ: John F. Kennedy and the Secret Cuban Missile Crisis Meetings 360-63, 365-66 (2003). Still, Rusk acknowledged that it was Thompsonʼs idea. James C. Blight & David A. Welch, On the Brink: Americans and Soviets Reexamine the Cuban Missile Crisis 179 (1989).

Rusk was reticent in this letter, since only 30 minutes of the ExComm tapes and sanitized transcripts of parts of the meetings on October 16 and October 27 had been released to the public by the time he wrote this letter. But Rusk knew—as we know now—that ultimately Kennedy took something of both positions. The ExComm meeting resulted in a letter from the President accepting the terms of Khrushchev's first letter. Then, outside of the ExComm, the President met secretly in the Oval Office with a small group that included Thompson, Rusk, and Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy. Unfortunately, that meeting was not taped. But it was there that the President also instructed Bobby to have a back-channel meeting with Soviet Ambassador Anatoly Dobrynin in order to convey clandestinely to Khrushchev that, although he could not publicly agree to remove American missiles from Turkey, the United States would dismantle those missiles in time. Echoing Thompsonʼs concerns, Bobby was told to emphasize that dismantling the missiles was not a trade. The dual diplomacy worked, and the Missile Crisis ended peacefully.

Rusk's assessment of Thompson as "one of the best of our career foreign services officers" reflects that of many others. Robert Kennedy recounted the respect that both he and President Kennedy had for Thompson. President Kennedy, he said, "liked Tommy Thompson. . . . Tommy Thompson he thought was outstanding. I also thought he was outstanding. He made a major difference. The most valuable people during the Cuban crisis were Bob McNamara and Tommy Thompson, I thought." Robert Kennedy In His Own Words: The Unpublished Recollection of the Kennedy Years 420 (Edwin O. Guthman & Jeffrey Shulman eds. 1988). In another letter that we are offering, President Lyndon B. Johnson told Thompson upon his second retirement as Ambassador to the Soviet Union that "few men in public life have been so intimately involved in the vital issues of our time. Very few have contributed so much to their resolution. You have been a model and an inspiration to the Foreign Service, and a source of strength to Secretary Rusk and to me, as you were to our predecessors." Click here to see that letter. When Thompson died, Secretary of State William P. Rogers called him "one of the outstanding diplomats of his generation."

Thompson served as the United States Ambassador to the Soviet Union under both President Kennedy and his predecessor, President Dwight D. Eisenhower. He joined the Foreign Service in 1928, and during his long and distinguished career he served as the United States Ambassador to Austria from 1955 to 1957 before Eisenhower first appointed him Ambassador to the Soviet Union in 1957. Kennedy reappointed him in 1961, but he resigned in 1962 to take the title of Ambassador At Large and serve as a key advisor to Kennedy and a member of his inner circle with respect to Soviet affairs. Johnson reappointed him to Moscow in 1967, and he served there until he retired in 1969. He was present at Johnson's summit with Soviet Premier Alexei Kosygin at Glassboro, New Jersey, in June 1967. He later came out of retirement to advise President Richard Nixon on the Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty (SALT) negotiations with the Soviet Union and to serve as a member of the United States delegation to the SALT talks from 1969 until his death in 1972.

This letter comes with a handwritten letter from Rosenfeld to Thompson's widow, Jane. Referring to the sanitized transcript of the October 27 ExComm meeting in which Thompson played a key role, Rosenfeld writes, in full: "Perhaps this letter will interest you. If you did not yet receive the Oct. 27 transcript, please tell me—Iʼll jog Harvard again. So many people share with me, after that column, their regard for Tommy." A copy of Rosenfeldʼs column also accompanies these pieces.

Rusk's letter is in fine condition. It has two horizontal mailing folds and some minor defects: staple holes at the upper left, Rusk's red receipt stamp in the blank upper right margin, and a small stain and a stray blue ink mark in the blank lower area. Rusk has signed in black with a small, old-age signature. Rosenfeldʼs letter has a vertical fold, scattered bends, and staple holes at the upper left. It is also in fine condition.

Provenance: These items come directly from the Thompson estate. They have never been offered on the autograph market before.

Unframed.

Click here to see other items from the Llewellyn E. Thompson Collection