1431402

Marquis de Lafayette

Jean-Sylvain Bailly

Scroll down to see images of the item below the description

Outstanding document signed by the heroes of the early French Revolution

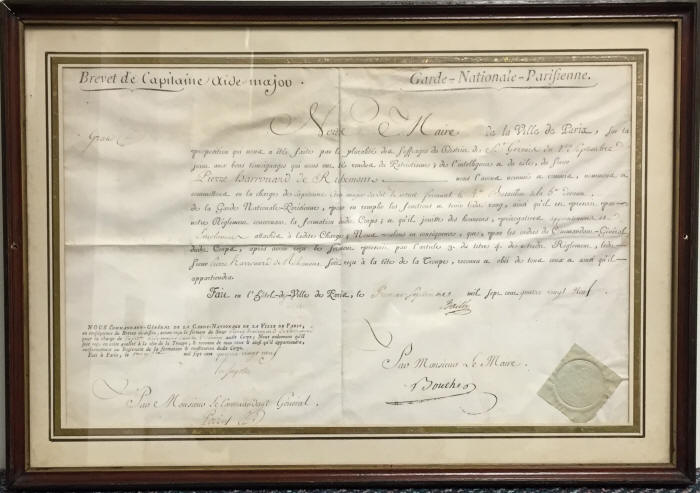

Jean-Sylvain Bailly, 1736–1793, French astronomer, mathematician, and political leader, and Marie-Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier de Lafayette, Marquis de Lafayette, 1757–1834, French aristocrat who supported the Americans during the Revolutionary War. Partially printed document signed Bailly and countersigned Lafayette, folio, Paris, September 1, 1789. In French. Untranslated.

This document is signed by the two undisputed heroes of the early French Revolution. It is a military commission for the French National Guard signed by Bailly, who served two years, 1789–1791, as the mayor of Paris, and countersigned by Lafayette, who had served with George Washington in aid of the American revolution, as the Commandant-General of the Guard.

Lafayette became a Field Marshal when he returned to France after serving Washington in the Revolutionary War. In December 1786, King Louis XVI appointed him to the Assembly of Notables, which had been convened to address Franceʼs economic woes. Louis XVI inherited the throne when France was mired in debt from the extravagance of his predecessors, Louis XIV and Louis XV. Lafayette advocated reform, decrying profiteering by those whose court connections gave them inside information about government land purchases, and called for a "truly national assembly" representing the whole of France. Louis XVI summoned an Estates-General to assemble in 1789.

The Estates-General was a general assembly comprising the three French estates of the realm: the clergy, the First Estate; the nobility, the Second Estate; and the rest of French society, essentially the common people, the Third Estate. It had not met since 1614. Lafayette was elected to represent the nobility from Riom, and Bailly was elected deputy from Paris.

The Estates-General convened at Versailles on May 5, 1789, but immediately deadlocked over the manner of voting. Lafayette favored voting by head, which would give the Third Estate control over the others. He could not convince the nobility to agree, but the clergy joined with the Third Estate, effectively wrestling control from the nobility.

On June 17, 1789, the group broke away from the Estates-General and declared itself to be the National Assembly. Bailly was elected the first president. Three days later, the 577 members of the Third Estate were locked out of the Estates-General, and soldiers guarded the chamber door. The members feared that the King would attack, so they gathered in a nearby indoor tennis court, where 576 of them took the "Tennis Court Oath." They resolved “that nothing can prevent" the National Assembly “from continuing its deliberations in whatever place it may be forced to establish itself" and that “wherever its members meet together, there is the National Assembly." They pledged themselves "never to separate and to reassemble wherever circumstances shall require until the constitution of the Kingdom shall be established and consolidated upon firm foundations." The Tennis Court Oath clearly defied the King, asserting that authority derived from the people, not from the monarch. Louis XVI was forced to direct the clergy and the nobility to join with the Third Estate in the National Assembly in order to create the appearance that he was in control.

Lafayette, whose leanings were with the common people, but who also supported the King, joined the new National Assembly. During this time, he was in consultation with Thomas Jefferson, who was in Paris as the United States Minister to France. On June 3, 1789, Jefferson wrote to Jean-Paul Rabaut Saint-Étienne, a leader of the French protestants and a moderate revolutionary who had been elected to the Estates-General as a member of the Third Estate, to report on his further conversation with Lafayette. After Saint-Étienne had left their meeting the night before, Jefferson said, “an idea was suggested, which appearing to make an impression on Monsr. de la Fayette, I was encouraged to pursue it on my return to Paris, to put it into form and now to send it to you & him." Jefferson sent a draft of a “Charter of Rights" that he suggested the King offer “to be signed by himself & by every member of the three orders." Essentially it was a settlement document enlarging legislative authority while retaining the rights of the sovereign. Nothing became of the proposal, but ultimately, on July 11, Lafayette introduced before the National Assembly a draft of the “Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen,” which he had written in close consultation with Jefferson.

Four days later, on July 15, the day after revolutionary rioters stormed the Bastille in Paris, Lafayette was named Commandant-General, or commander-in-chief, of the National Guard, which likewise had its genesis in the political unrest that fueled the revolution. The same day, Bailly was named the first mayor of Paris.

The Guard was a militia, separate from the French Army, that acted as a police force under the control of the National Assembly to maintain law and order and as military reserve. The first units were formed in Paris in the summer of 1789 from middle-class volunteers who had defected from the French Guards, the infantry regiment of the household of the King, to the revolutionary cause and from former members of the Paris Guard. Similar forces were created in the towns and rural districts in response to fears of chaos or counter-revolution. The National Guard, and particularly its officers, were widely seen as loyal to middle-class interests. When the French Guards mutinied and were disbanded in July 1789, most of its soldiers became members of the National Guard.

On July 17, Bailly ordered that Lafayetteʼs National Guard disperse crowds demanding removal of the King. When the crowd refused to disperse, the Guard fired directly into the crowd. A number of people were killed in what became known as the Champ de Mars Massacre.

As Commandant-General, Lafayette tried to steer a middle ground between the King and the radicals, led by the extremist Jacobins, the Society of Friends of the Constitution. The King and those loyal to him thought that Lafayette was a revolutionary, while many commoners thought that he was trying to help keep the King in power. His troops successfully prevented an violent crowd that stormed the palace at Versailles from seizing the royal family, but on October 6 the King and the royal family moved from Versailles to Paris under the protection of the National Guard, thus legitimizing the National Assembly.

Ultimately, as factions developed within the National Assembly, Lafayette, Bailly, and other centrists were unsuccessful in preventing the extremist Jacobins, from radicalizing the revolution. Lafayette, by then in Austria in command of French troops, wrote to the National Assembly on June 16, 1792, denouncing the policies of the Jacobins, and appeared in person on June 28. But Lafayette found Paris controlled by the radicals. He plotted to remove the King from Paris, but on August 10, Louis XVI was arrested and imprisoned. The National Assembly declared France to be a Republic and abolished the monarchy. When Lafayette then refused to obey the orders of the National Assembly, it removed him from command, and when he fled to Belgium, he was seized by the enemy and ultimately imprisoned by the Prussians. Louis XVI was tried for treason and guillotined in the Place de la Révolution, now the Place de la Concorde, on January 21, 1793.

Bailly was unpopular because of the Champ de Mars Massacre. He had retired to write his memoirs, but he was recognized and arrested at Melun, tried before the Revolutionary Tribunal in Paris, and guillotined at the Champ de Mars—the location was no coincidence—on November 12, 1793. After several years in prison, Lafayette was freed by the victories of Napoleon Bonaparte.

This is a bright, clean document that has not been on the autograph market for some 70 years. It comes from a collection that was assembled in the 1940s.

The document is also countersigned by Charles François Bouche (1737–1795), a deputy of the Estates-General in 1789, for Bailly. It has intersecting horizontal and vertical folds. The paper and wax seal is intact at the lower right. The document has been matted in an ornate gilded mat and framed in a vintage frame. We have not examined the document out of the frame, but it appears to be in fine condition.

Please click here to contact us regarding the availability of this item.