1507101

John Hancock

Scroll down to see images of the item below the description

Amid fervor to declare independence from Great Britain,

Hancock signs congressional resolutions to raise battalions of troops

to fortify Boston against a possible British attack

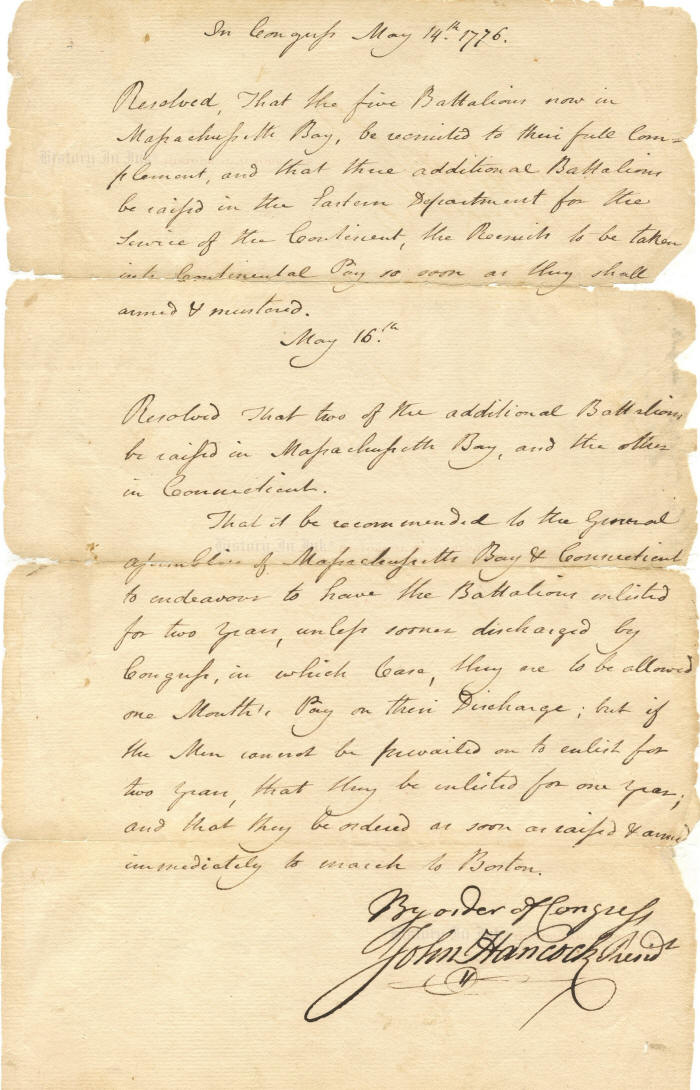

John Hancock, 1737–1793. First signer of the American Declaration of Independence. Superb Manuscript Document Signed, John Hancock Presid t, one page, 8" x 12", In Congress [Philadelphia, Pennsylvania], May 16, 1776.

This document reflects the American commitment to sever ties with Great Britain at the price of bloodshed. In a hurried move to fortify Boston against a possible imminent attack by the British—and in the midst of action toward declaring independence from Great Britain—Hancock signs congressional resolutions authorizing recruitment of battalions of troops "to be ordered as soon as raised & armed immediately to march to Boston." Hancock has signed “By order of Congress" with his classic huge signature and paraph, adding his title.

The recently-ended Siege of Boston provides the backdrop for these resolutions. General George Washington, with too few troops to defend Boston after moving the Continental Army to fortify New York, sought congressional action in light of intelligence that British ships loaded with German mercenary soldiers were sailing for America.

The British had occupied Boston for several years after Parliament enacted a series of trade regulations such as the 1765 Stamp Act, which imposed taxes on printed materials, and the 1767 Townshend Acts, which led to taxation on goods. Violence erupted in 1770, when British soldiers fired on a group of protesting colonists, killing five men in what became known as the Boston Massacre. Parliament repealed most of the Townshend Acts but kept the tax on tea. Tensions flared again in 1773, when Massachusetts protesters dressed as Indians boarded British ships and dumped their cargoes of tea into Boston Harbor—the Boston Tea Party—which led Parliament to reassert its authority through more legislation. At the urging of Hancock and others such as Washington, Samuel Adams, John Jay, and Patrick Henry, in 1774 the Continental Congress denounced Britain for imposing taxes on the colonies without representation in Parliament and for headquartering troops in the colonies without their permission.

In April 1775, colonial militiamen fought the British at the battles of Lexington and Concord, the first shots fired in the Revolutionary War, as the British sought to arrest Hancock and Adams and destroy colonial military supplies at Concord. The colonists drove the British back to Boston and then encircled the city with 15,000 troops in an effort to contain them there. Britain reinforced its army by sea, however, since the Americans had no navy, and attacked the colonists on Breedʼs Hill on the heights above Boston. The British won what became known as the Battle of Bunker Hill on June 17, 1775, claiming the heights on the Charlestown Peninsula, but the colonists secured an important psychological victory by inflicting significant damage on the British Army.

The next month, Washington arrived in Boston to assume command of the Continental Army. Using cannons that the Americans had captured from the British at New Yorkʼs Fort Ticonderoga, Washingtonʼs army bombarded Boston for two days in early March 1776 before Washington moved more troops and cannon into position on Dorchester Heights above the city and Boston Harbor. Knowing that he could not dislodge the Americans, British General William Howe resolved to withdraw. The Siege of Boston and Britainʼs eight-year occupation of the city ended on March 17, 1776, when Howeʼs army sailed for Nova Scotia.

Washington hurried the Continental Army to New York, recognizing its strategic “infinite importance" at the mouth of the Hudson River and believing that the British might instead be sailing there. Although he left five regiments at Boston, four of them were only about half strength. Further reducing the strength of his army, Washington sent two brigades, comprising 10 divisions, to Canada in support of the Quebec campaign.

On May 7, 1776, Washington received intelligence that British ships carrying German Hessian mercenary soldiers were on the way. Separate reports came from Major General Artemas Ward, who was in command of the troops in Boston, and from Thomas Cushing, a former member of the Continental Congress. Both wrote Washington on May 3 and ultimately relied on information passed along by Captain John Lee, a shipmaster whom Cushing described as “a Gentleman who may be depended upon." Lee had just arrived at Newbury, Massachusetts, north of Boston, after sailing 29 days from Bilbao, Spain.

Ward wrote that Lee said that on April 14,

in longitude 45, from London he spoke a Vessel from Plymouth in England, who informed him that three days before he parted with a fleet of sixty sale of Transports bound for Boston under the Command of Admiral Howe, having on board twelve thousand Hessian Troops; that twenty seven Commissioners were on board this fleet, that they were directed if possible to adjust matters with the Colonies; if not, to penetrate at the risque of every thing, into the Country; if this could not be effected, then to burn and destroy all in their power; that [British] Genl [John] Burgoyne was near sailing with four thousand Hanoverians for Quebec; [and] a number of Regiments are gone to the Southern Colonies . . . .

Thus, by this account, the Hessian troops had sailed from Plymouth on April 11, nearly a month before Washington received the report.

Cushing passed along a letter from Timothy Pickering, Jr., of the Salem Committee of Safety, which had, in turn, received information from Lee through Richard Derby, Jr., of Newbury. Pickering said that Lee had read in the British newspapers “that the Parliament had voted pay for the foreign troops." By his account, Lee had spoken with the ship from Plymouth on April 15, a day later than Ward had said. The Salem committee reported that Lee had carried a letter from merchant Joseph Gardoqui, whose family company represented the American interests before the Spanish royal court. Gardoqui had written to Isaac Smith on March 27 that there was no news from England “but that 17,300 German troops were going to Boston and Canada some of which were embarking about 3 Weeks ago." Cushing suggested to Washington that “as the British Troops left this Colony in Disgrace,” they might “return here to retrieve their Character,” and thus he asked Washington to “reinforce the Detachment under General Wardʼs Command, as soon as may be; as the Regiments under his Command are by no means full."

With sailing time of a month or less between England and North America, these reports meant that the Hessian troops could arrive any day if they had not already arrived, whether in Canada or somewhere in the colonies.

Washington was somewhat skeptical, since the number of troops mentioned in the reports did not match the number of ships, but nonetheless he was both cautious and anxious. Upon receiving the intelligence, he wrote immediately to Hancock to request instructions:

At a quarter after Seven this Eveng, I received by Express a Letter from Thos Cushing Esqr., Chairman of a Committee of the Honorable Genl Court, covering one to them from the Committee of Salem, Copies of which I do myself the Honor to lay before Congress, that they may Judge of the Intelligence contained therein, and direct such measures to be taken upon the occasion as they may think proper and necessary. I wou'd observe, that supposing Captn Lees account to be true in part, I think there must be a mistake either in the number of Troops or the Transport Ships; If there are no more Ships than what are mentioned It is certain there can not be so many Troops, of this however Congress can Judge as well as myself, and I submit It to them, whether upon the whole of the circumstances & the uncertainty of their destination If they were seen at all, they chuse that any forces shall be detached from hence, as they will see from the Returns transmitted Yesterday that the number of men now here is but small and inconsiderable & what is to be regretted, no small part of those without Arms—Perhaps by dividing & Subdividing our force too much we shall have no one post sufficiently guarded—I shall wait their direction & whatever their order is, shall comply with It as soon as possible. . . .

P.S. I have by the express a Letter from Genl Ward containing a Similar Act to that from the Salem Come, & by way of Capn Lee.

Shouʼd the Commissioners arrive which are mentioned How are they to be received & treated? I wish the direction of Congress upon the Subject by return of the Bearer.

Congress appointed a committee to consider the issue. On May 10, the committee recommended that Congress urge Massachusetts “to assist the Officers of the five Continental Regiments now in that Colony in compleating their Enlistment" and that “they endeavour to prevail on their People to enlist, and those already enlisted to re-enlist for 3 years, unless sooner discharged, and then to receive a mo. pay." It also recommended that Washington “be desired to send such Genl. Officer as he can spare from the Army at New York to command in the Colony of Massachusetts Bay." Congress debated the issue further, however, and on May 14 and 16 it enacted the resolutions that appear in this document:

In Congress May 14th 1776

Resolved, That the five Battalions now in Massachusetts Bay, be recruited to their full Complement, and that three additional Battalions be raised in the Eastern Department, for the service of the Continent, the Recruits to be taken into Continental Pay so soon as they shall be armed & mustered.

May 16.th

Resolved, that two of the additional Battalions be raised in Massachusetts Bay, and the others in Connecticut.

That it be recommended to the general Assemblies of Massachusetts Bay & Connecticut to endeavor to have the Battalions enlisted for two years, unless sooner discharged by Congress, in which Case they are to be allowed one Monthʼs Pay on their Discharge; but if the Men cannot be prevailed on to enlist for two years, that they be enlisted for one year; and that they be ordered as soon as raised & armed immediately to march to Boston.

On May 16, Hancock wrote letters to forward copies of these resolutions. He sent one to General Washington, suggesting, although stressing that he "would not urge a Matter which entirely rests with you,” that Washington send Major General Horatio Gates and Brigadier General Thomas Mifflin to Boston. He also sent the resolutions to the general assemblies of Massachusetts Bay and Connecticut. To the Massachusetts Assembly, he wrote:

By the best Intelligence from Europe it appears, That the British Nation have proceeded to the last Extremity, and have actually taken into Pay a Number of foreign Troops; who, in all Probability, are on their Passage to America at this very Time. The Transactions of the Ministry are so much hid from View, that we are left to wander in the Field of Conjecture; and it is entirely to accident we are indebted, for any little Information we may receive with Regard to their Designs against us. This Uncertainty however, I hope, will have the proper Effect. It should stimulate the Colonies to greater Dilligence [sic] & Vigour in preparing to ward off the Blow, as our Enemies may, for any Thing we know, be at our very Door.

In this Situation of our Affairs, it is highly necessary, that the Town of Boston should receive a Reinforcement, to prevent it from falling again into the Hands of such Miscreants, as have just been driven out of it. The Congress therefore considering the small Number of Troops in that Place, and the Impossibility of detaching any from the Continental Army which has lately been much weakened by the two Brigades consisting of Ten Regiments ordered into Canada, have come to the enclosed Resolutions, which I am commanded to transmit you, being fully assured, that you will do every Thing possible in your Power to carry the same into Effect as speedily as possible.

Hancockʼs vitriol against Britain reflects the independence fervor that had reached a boiling point in Congress as it enlarged the Continental Army with these resolutions. At the same time, Congress debated independence. On May 10, 1776, it had enacted the following resolution, with language that would appear six weeks later, in modified form, in the Declaration of Independence:

Resolved, That it be recommended to the respective assemblies and conventions of the United Colonies, where no government sufficient to the exigencies of their affairs have been hitherto established, to adopt such government as shall, in the opinion of the representatives of the people, best conduce to the happiness and safety of their constituents in particular, and America in general.

In other words, Congress authorized the colonies to throw off the British crown in favor of self-government. It appointed a committee of three, John Adams, Edward Rutledge, and Richard Henry Lee, to draft the preamble to the resolution. The committee submitted a draft on Monday, May 13, which was read and further consideration of it postponed until the following day.

The preamble, which Adams wrote, recited:

Whereas his Britannic Majesty, in conjunction with the lords and commons of Great Britain, has, by a late act of Parliament, excluded the inhabitants of these United Colonies from the protection of his crown; And whereas, no answer, whatever, to the humble petitions of the colonies for redress of grievances and reconciliation with Great Britain, has been or is likely to be given; but, the whole force of that kingdom, aided by foreign mercenaries, is to be exerted for the destruction of the good people of these colonies; And whereas, it appears absolutely irreconcileable [sic] to reason and good Conscience, for the people of these colonies now to take the oaths and affirmations necessary for the support of any government under the crown of Great Britain, and it is necessary that the exercise of every kind of authority under the said crown should be totally suppressed, and all the powers of government exerted, under the authority of the people of the colonies, for the preservation of internal peace, virtue, and good order, as well as for the defence of their lives, liberties, and properties, against the hostile invasions and cruel depredations of their enemies; therefore, resolved, &c.

On May 15, after vigorous debates over three days, Congress approved the preamble and ordered that it be published along with the resolution passed on May 10. To his wife, Abigail, John Adams wrote that Great Britain had “at last driven America, to the last Step, a compleat Seperation from her, a total absolute Independence, not only of her Parliament but of her Crown, for such is the Amount of the Resolve of the 15th." In a letter to James Warren, Adams called it ”the most important Resolution, that ever was taken in America."

This document bears an absolutely magnificent Hancock signature, one that Hancock signed with the boldness of his signature that appears on the Declaration of Independence. Hancockʼs classic paraph appears beneath his signature.

The signature has not been affected by other defects, which have been professionally repaired. The document has considerable edge chipping, with accompanying paper loss, but only part of one letter of the text is affected. Detached fragments have been reattached and breaks in the two horizontal folds, affecting part of the text, have been mended using mulberry paper and rice starch paste. Old paper and pressure-sensitive tape previously used to stabilize the document on the back have been removed, along with the residual adhesive. Overall the document is in fair to good condition.

This is a superb, significant document from the tense weeks in the Continental Congress leading up to adoption of the formal Declaration of Independence. It belongs in the finest of Revolutionary War or American History collections.

Unframed.

Please click here to contact us about the availability of this item.