1618701

George C. Wallace

“I will continue to stand firm for state sovereignty and constitutional government.

. . . I am unalterably opposed to the misnamed civil rights bill . . . ”

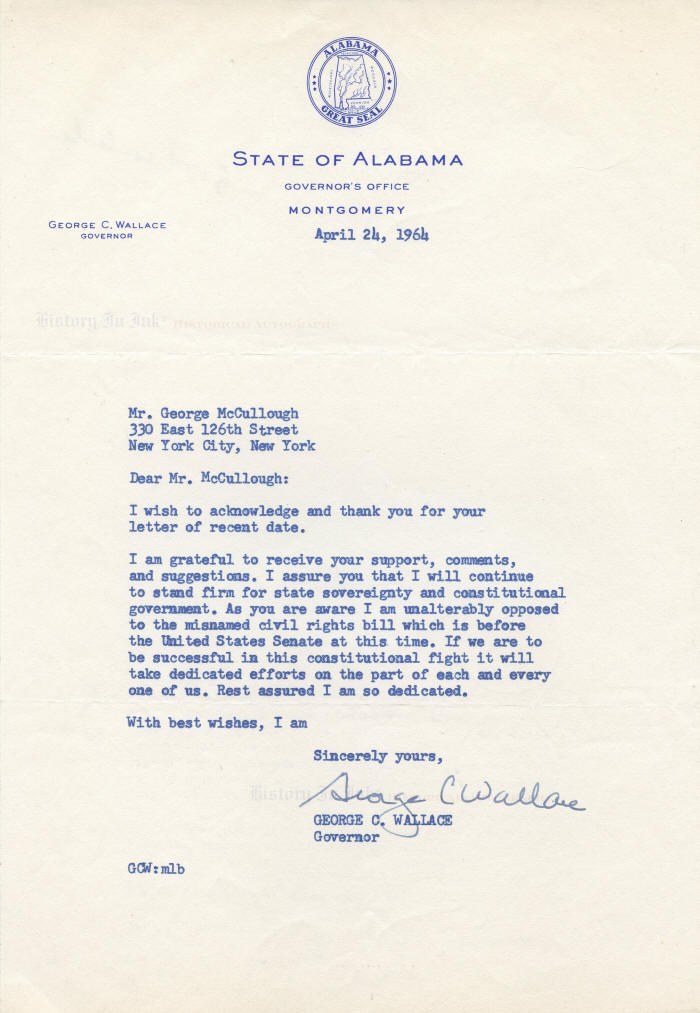

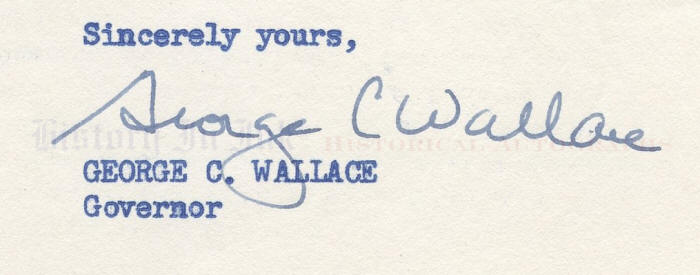

George Corley Wallace, Jr., 1919–1998. Governor of Alabama, 1963–1967, 1971–1979, 1983–1987; four-time American presidential candidate. Superb Typed Letter Signed, George C. Wallace, one page, 7¼” x 10½”, on stationery of the State of Alabama, Montgomery, [Alabama], April 24, 1964.

At his first inauguration as Governor of Alabama in January 1963, Wallace vitriolically rejected federal efforts, which he deemed tyrannical toward the South, to ban racial discrimination. “In the name of the greatest people that have ever trod this earth,” he proclaimed, “I draw the line in the dust and toss the gauntlet before the feet of tyranny, and I say segregation now—segregation tomorrow—segregation forever.” A Montgomery newspaper reporter described the speech as “vehement,” “mean spirited,” and “hateful,” “like a rattlesnake was hissing it, almost.” Fifty years later, NPR called it “one of the most vehement rallying cries against racial equality in American history.”

In this extraordinary letter—by far the finest content Wallace letter we have seen—the defiant Governor emphasizes to a supporter his absolute opposition to the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which was then pending in Congress. He writes: “I am grateful to receive your support, comments, and suggestions. I assure you that I will continue to stand firm for state sovereignty and constitutional government. As you are aware I am unalterably opposed to the misnamed civil rights bill which is before the United States Senate at this time. If we are to be successful in this constitutional fight it will take dedicated efforts on the part of each and every one of us. Rest assured I am so dedicated.”

Among other things, the Civil Rights Act, which President Lyndon B. Johnson signed in July 1964, barred racially unequal application of voter registration requirements; prohibited racial discrimination in hotels, motels, restaurants, theaters, and other places of public accommodation engaged in interstate commerce; prevented state and local governments from denying access to public facilities on grounds of race, color, religion, and national origin; authorized the Attorney General to file suit to enforce public school desegregation; and expanded the power of the federal Civil Rights Commission.

Wallace began his career in 1945 as an Alabama Assistant Attorney General before being elected to the state House of Representatives in 1946. Although he opposed President Harry S. Truman’s proposed civil rights program as an infringement of states’ rights, he did not join the Dixiecrat walkout at the 1948 Democratic convention. Nevertheless, subsequently, as a state circuit judge, although he was seen as a moderate, Wallace became the first Southern judge to enjoin the removal of segregation signs in railroad terminals.

In 1958, Wallace lost Alabama’s Democratic gubernatorial primary, which, given the primacy of the Democratic Party in Alabama at the time, was effectively the election that decided the governorship. His opponent had received the support of the Ku Klux Klan, while Wallace, who had refused it, had the support of the NAACP.

The loss turned Wallace into a boiling segregationist. He explained to an aide that he had lost because he had been “out-N__ed. . . . And I’ll tell you here and now, I will never be out-N__ed again.”

He won the next gubernatorial election in 1962. He took the oath of office as Governor on January 14, 1963, standing on a gold star at the Alabama state capitol marking the spot where Jefferson Davis had been sworn in as provisional President of the Confederate States of America in 1861. He noted that he stood where Davis once stood. “It is very appropriate then,” he said, “that today we sound the drum for freedom as have our generations of forbears before us done, time and again down through history. Let us rise to the call of freedom-loving blood that is in us and send our answer to the tyranny that clanks its chains upon the South.” His answer: “segregation forever.”

To make good on his promise of segregation—and to generate publicity for himself with white voters—on June 11, 1963, Wallace personally blocked the door to Foster Auditorium at the University of Alabama to prevent the enrollment of African-American students pursuant to a federal district court order. Accompanied by federal marshals, U.S. Deputy Attorney General Nicholas deB. Katzenbach asked Wallace to step aside. Wallace, wearing a microphone, with a speaker’s stand set before him, and surrounded by officers of the Alabama Highway Patrol, interrupted Katzenbach and delivered a speech decrying federal infringement of states’ rights. “The unwelcomed, unwanted, unwarranted and force-induced intrusion upon the campus of the University of Alabama today of the might of the Central Government offers frightful example of the oppression of the rights, privileges and sovereignty of this State by officers of the Federal Government,” Wallace said. “This intrusion results solely from force, or threat of force, undignified by any reasonable application of the principle of law, reason and justice. . . . I stand here today, as Governor of this sovereign State, and refuse to willingly submit to illegal usurpation of power by the Central Government.”

Katzenbach telephoned President John F. Kennedy, who federalized the Alabama National Guard. The commander of the guard, General Henry Graham, then asked Wallace to step aside, declaring it his “sad duty . . . under the orders of the President of the United States.” Wallace ultimately stepped aside, and the students registered.

Wallace sought the presidency in 1964 but soon dropped out of the race. He ran again in 1968, mounting a strong third-party candidacy against incumbent Vice President Hubert H. Humphrey, the Democratic nominee, and former Vice President Richard Nixon, the Republican nominee who had lost to Kennedy in 1960. Wallace, who was a Democrat as Alabama’s governor, advocated increases in both Social Security and Medicare but also ran a conservative law-and-order campaign. Both Humphrey and Nixon feared that Wallace would split the vote among their own supporters and pave the way to victory for the other. Wallace disavowed any racist philosophy, saying that he wanted the support of “people of all races and colors,” and argued that “the worst bigots in the country are those who call other people bigots.” He said, however, that if elected president he would ask Congress to repeal a federal law enacted to prohibit racial discrimination in the sale of housing. In the end, Wallace garnered some 10 million votes, carried five Southern states, and received 46 electoral votes.

He went on to run for president twice more. In 1972, he announced that he no longer supported segregation and claimed that he had always been a moderate on racial matters. While campaigning in Maryland, he was shot five times in rapid succession in an assassination attempt. One of the bullets lodged in his spine, leaving him paralyzed from the waist down. He campaigned in his wheelchair in 1976 but dropped out of the race and eventually endorsed Georgia Governor Jimmy Carter, who became the Democratic nominee.

Wallace announced in the late 1970s that he had become a Christian, and he apologized to African-American civil rights leaders for his past actions. He disavowed as wrong his stand at the door of the University of Alabama. He was elected Governor once more, in 1982, and in his last administration appointed a record number of African-Americans to state positions. At least one writer questioned his conversion, however, arguing that Wallace was never serious in his claim that he was a segregationist, not a racist.

PBSʼs American Experience called Wallace “the most influential loser in American history.” Writers at the time of his death in 1998 argued that his 1968 campaign set the course for Republican dominance in American society, with Nixon, Ronald Reagan, and George H. W. Bush adopting diluted versions of Wallace’s strong anti-federal government platform.

This letter is in very fine condition. Wallace has signed in blue fountain pen. The letter has two horizontal mailing folds, which do not affect either the typewritten text or Wallace’s signature. There is a light pencil notation in another hand on the back.

We reject racism in any form. We nevertheless offered this item because of the significant impact that Wallace had on American political thought in the second half of the 20th Century.

Unframed.

_____________

This item has been sold, but

click here to see other

American History items

that we are offering.